Badminton

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Sports

Badminton is a racquet sport played by either two opposing players (singles) or two opposing pairs (doubles). The players or pairs take positions on opposite halves of a rectangular court that is divided by a net.

Unlike many racquet sports, badminton does not use a ball: badminton uses a feathered projectile known as a shuttlecock. Since the shuttlecock is strongly affected by wind, competitive badminton is always played indoors.

General Description

The players strike the shuttlecock with their rackets so that it passes over the net and into the opponents' half of the court. The rally ends once the shuttlecock touches the ground: every stroke must be played as a volley. In doubles, either player of a pair may hit the shuttlecock (except on service), but only a single stroke is allowed before the shuttlecock passes again into the opponents' court. Players are awarded a point if the shuttlecock lands on or within the marked boundary of their opponents' court, or if their opponent's stroke fails to pass the net or lands outside the court boundary.

A rally begins with the service, in which the serving player must strike the shuttlecock so that, if left, it would land in the diagonally opposite service court. In doubles, only one player, the receiver, may return the service (thereafter either player may hit the shuttlecock); the order of doubles service is determined by the Laws, which ensure that all the players shall serve and receive in turn. If the server wins the rally, he will continue serving; if he loses the rally, the serve will pass to his opponent. In either case, the winner will add a point to his score.

A match consists of three games; to win each game players must score 21 points (exceptions noted below). There are five events: men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles, women's doubles, and mixed doubles (each pair is a man and a woman).

History and development

Badminton is widely believed to have originated in ancient Greece about 2000 years ago. From there it spread via the Indo-Greek kingdoms to Indian and then further east to China and Siam (now Thailand).

In England since medieval times a children's game called Battledore and Shuttlecock was popular. Children would use paddles (Battledores) and work together to keep the Shuttlecock up in the air and prevent it from reaching the ground. It was popular enough to be a nuisance on the street of London in 1854 when the magazine Punch published a cartoon depicting it.

In the 1860s, British Army officers in Pune, India, began playing the game of Battledore and Shuttlecock, but they added a competitive element by including a net. As the city of Pune was formerly known as Poona, the game was known as Poona at that time.

About this same time, the Duke of Beaufort was entertaining soldiers at his estate called " Badminton House", where the soldiers played Poona. The Duke of Beaufort’s non-military guests began referring to the game as "the badminton game", and thus the game became known as "badminton".

In 1877, the first badminton club in the world, Bath Badminton Club, transcribed the rules of badminton for the first time. However, in 1893, the Badminton Association of England published the first proper set of rules, similar to that of today, and officially launched badminton in a house called 'Dunbar' at 6 Waverley Grove, Portsmouth, England on September 13 of that year. They also started the All England Open Badminton Championships, the first badminton competition in the world, in 1899.

The International Badminton Federation (IBF) was established in 1934 with Canada, Denmark, England, France, the Netherlands, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, and Wales as its founding members. India joined as an affiliate in 1936. The IBF now governs international badminton and develops the sport globally.

Scoring system development

In the traditional scoring system, games were played to 15 points, except for women's singles which was played up to 11. A match was decided by the best of three games. Only the serving players were able to score a point. In doubles, both players of a pair would serve before the service returned to the other side: in order to regain the service, the receiving pair had to win two rallies (not necessarily consecutively).

In 1992, the IBF introduced new rules: setting at 13-all and 14-all. This meant that if the players were tied at 13-13 or 14-14 (9-9 or 10-10 for women's singles), the player who had first reached that score could decide elect to set and play to 17 (or to 13 for women's singles).

In 2002 the IBF, concerned with the unpredictable and often lengthy time required for matches, decided to experiment with a different scoring system to improve the commercial and especially the broadcasting appeal of the sport. The new scoring system shortened games to 7 points and decided matches by the best of 5 games. When the score reached 6-6, the player who first reached 6 could elect to set to 8 points.

Yet the match time remained an issue, since the playing time for the two scoring systems was similar. This experiment was abandoned and replaced by a modified version of the traditional scoring system. The 2002 Commonwealth Games is the last event used this scoring system.

In December 2005 the IBF experimented again with the scoring system, intending both to regulate the playing time and to simplify the system for television viewers. The main change from the traditional system was to adopt rally point scoring, in which the winner of a rally scores a point regardless of who served; games were lengthened to 21 points. However, the new scoring system makes the game duration significantly shorter. The experiment ended in May 2006, and the IBF ruled that the new scoring system would be adopted from August 2006 onwards. This scoring system is described in full in Scoring system and service, below.

Laws of the Game

The following information is a simplified summary of the Laws, not a complete reproduction. The definitive source of the Laws is the IBF Laws publication, although the digital distribution of the Laws contains poor reproductions of the diagrams.

Playing court dimensions

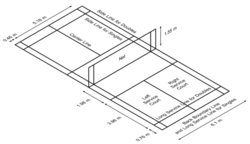

The court is rectangular and divided into halves by a net. Courts are almost always marked for both singles and doubles play, although the laws permit a court to be marked for singles only. The doubles court is wider than the singles court, but the doubles service court is shorter than the singles service court.

The full width of the court is 6.1 metres, and in singles this width is reduced to 5.18 metres. The full length of the court is 13.4 metres. The service courts are marked by a centre line dividing the width of the court, by a short service line at a distance of 1.98 metres from the net, and by the outer side and back boundaries. In doubles, the service court is also marked by a long service line, which is 0.78 metres from the back boundary.

The net is 1.55 metres (5 ft 1 inch) high at the edges and 1.524 metres (5 ft) high in the centre. The net posts are placed over the doubles side lines, even when singles is played.

Surprisingly, there is no mention in the Laws of a minimum height for the ceiling above the court. Nonetheless, a badminton court will not be suitable if the ceiling is likely to be hit on a high serve.

Equipment laws

The Laws specify which equipment may be used. In particular, the Laws restrict the design and size of rackets and shuttlecocks. The Laws also provide for testing a shuttlecock for the correct speed:

- 3.1

- To test a shuttle, use a full underhand stroke which makes contact with the shuttle over the back boundary line. The shuttle shall be hit at an upward angle and in a direction parallel to the side lines.

- 3.2

- A shuttle of the correct speed will land not less than 530 mm and not more than 990 mm short of the other back boundary line....

Scoring system and service

A point shall be added to a player's score whenever he wins a rally.

A match consists of the best of three games; a game is won by the first player to score 21 points, except if the score reaches 20 points each; in this case, play shall continue until one player either achieves a two point lead (such as 24-22), or his score reaches 30 (the score shall not extend beyond 30: 30-29 is a winning score).

At the start of a match a coin toss is conducted between the players or pairs. The winners of the coin toss may make one of two choices: they may choose whether to serve or receive first, or they may choose which end of the court they wish to occupy. After they have made this choice, their opponents shall exercise the remaining choice. In less formal settings, the coin toss is often replaced by hitting a shuttle into the air: whichever side it points to shall serve first.

In subsequent games, the winners of the previous game shall serve first. For the first rally of any doubles game, the serving pair may decide who serves and the receiving pair may decide who receives. The players shall change ends at the start of the second game; if the match proceeds to a third game, the players shall change ends both at the start of the game and when the leading pair's score reaches 11 points.

In singles, the server shall stand in his right service court when his score is even, and in his left service court when his score is odd; his opponent shall stand in the diagonally opposite service court.

In doubles, the players shall remember their service positions from the previous rally; the receivers shall remain in the same service courts. When a receiving pair wins a point and thereby regains the service, they shall not change their service court positions. If their new score is even, then the player in the right service court shall serve; if their new score is odd, then the player in the left service court shall serve. Thereafter, if they continue to win points, the server shall alternate between the service courts, so that he serves to each receiver in turn.

There are several notable consequences of this system. First, rally point scoring ensures that the start of the game is fairer than under the older scoring system; without rally point scoring, serving at the start of the game is a significant advantage. Second, there is no "second server", unlike under the older scoring system. Third, each time a pair regains the service, the service court laws ensure that the server shall be the player who did not serve last.

The server and receiver must remain within their service courts, so that their feet do not touch the boundary lines, until the server strikes the shuttle. The other two players may stand wherever they wish, so long as they do not unsight the opposing server or receiver.

Faults

Players win a rally by striking the shuttle onto the floor within the boundaries of their opponents' court. Players also win a rally if their opponents commit a fault. The most common fault in badminton is when the players fail to return the shuttle so that it passes over the net and lands inside their opponents' court, but there are also other ways that players may be faulted. The following information lists some of the more common faults.

Several faults pertain specifically to service. A serving player shall be faulted if he strikes the shuttle from above his waist (defined as his lowest rib), or if his racket is not pointing downwards at the moment of impact. This particular law changed in 2006: previously, the server's racket had to be pointing downwards to the extent that the racket head was below the hand holding the racket; now, any angle below the horizontal is acceptable.

Neither the server nor the receiver may lift a foot until the shuttle has been struck by the server. The server must also initially hit the base (cork) of the shuttle, although he may afterwards also hit the feathers as part of the same stroke. This law was introduced to ban an extremely effective service style known as the S-serve or Sidek serve, which allowed the server to make the shuttle spin chaotically in flight.

Each side may only strike the shuttle once before it passes back over the net; but during a single stroke movement, a player may contact a shuttle twice (this happens in some sliced shots). A player may not, however, hit the shuttle once and then hit it with a new movement, nor may he carry and sling the shuttle on his racket.

It is a fault if the shuttle hits the ceiling.

Lets

If a let is called, the rally is stopped and replayed with no change to the score. Lets may occur due to some unexpected disturbance such as a shuttle landing on court (having being hit there by players on an adjacent court).

If the receiver is not ready when the service is delivered, a let shall be called; yet if the receiver makes any attempt to return the shuttle, he shall be judged to have been ready.

There is no let if the shuttle hits the tape (even on service).

Equipment

Racquet: A racquet is a vital piece of equipment in badminton. Traditionally racquets were made of wood. Later on, aluminium or other light metals became the material of choice. Badminton racquets are composed of carbon fibre composite ( graphite reinforced plastic), with titanium composites ( nanocarbon) added as extra ingredients. Carbon fibre has an excellent strength to weight ratio, is stiff, and gives excellent kinetic energy transfer. They are two types of racquet: isometric (square) and oval. Racquets normally weigh between 80-95 g but weight differs between manufacturers, as it can affect how fast the racquet can swing.

Grip: Grip is the interface between the player's hand and the racquet. Type, size and thickness are three characteristics that affect the choice of grip. There are two types of grips: synthetic and towel. Synthetic grips are less messy and provide excellent friction. Towel grips are usually preferred as they are usually more comfortable and absorbent of sweat. Both have disadvantages as synthetic grips can deteriorate if too much sweat is absorbed and towel grips need to be changed often.

String: Perhaps one of the most overlooked areas of badminton equipment is the string. Different types of string have different response properties. Durability generally varies with performance. Most strings are 21 gauge in thickness and strung at 18 to 30 lbf (80 to 130 newtons) of tension. Racquets strung at lower tensions (18 to 21 lbf or 80 to 95 N) generate greater power while racquets strung at higher tensions provide greater control (21 lbf, over 95 N). Simply, a higher tension rewards hard hitting, while it robs power from a light hitter. Conversely, a lower tensioned string helps light hitter with a better timed trampoline effect.

Shuttlecock: A shuttlecock has an open conical shape, with a rounded head at the apex of the cone, they are made of cork and overlapped by sixteen goose feathers. There are different speeds and weights, but for easy classification, 75 is regarded as slow and 79 is the fastest shuttlecock. The feather shuttle is fairly brittle and thus for economical reasons this has been replaced by the use of a plastic (usually nylon) or rubber head and a plastic (usually nylon) skirt for practice use.

Shoes: Because acceleration across the court is so important, players need excellent grip with the floor at all times. Badminton shoes need gummy soles for good grip, reinforced side walls ( lateral support) for durability during drags, and shock dispersion technology for jumping; badminton places a lot of stress on the knees and ankles. Like most sports shoes, they are also light weight. They have a thin but well supported sole with good lateral support to keep the player’s feet close to the ground, allowing for speed and ankle bending directional changes with lower chance of injury; light weight for faster foot movement.

Basic strokes

There are many strokes in badminton; below is a list of basic strokes, which is divided into strokes played from the forecourt, midcourt, and rearcourt (the forecourt is the part of the court near the net, the rearcourt is the part of the court farthest away from the net, and the midcourt is the area in between them).

This list does not include every possible stroke, but only the strokes that are commonly played from that part of the court. The descriptions also assume that the players are of a very high standard and are making sensible choices of strokes.

Strokes played from the forecourt

-

- Serve

- The serve begins a rally. Serves are subject to several service laws that limit the attacking potential for service. The overall effect of these laws is that the server must hit in an upwards direction; "tennis serves" are prohibited. The serve is always cross court (diagonal).

-

- Low serve

- The low serve travels into the receiver's forecourt, to fall on or just after the opponents short service line. Low serves must travel as close to the net tape as possible, or they will be attacked fiercely. In doubles, the straight low serve is the most frequently used service variation.

-

- High serve

- The high serve is hit very high, so that the shuttle falls vertically at the back of the receiver's service court. The high serve is never used in doubles, but is common in singles.

-

- Flick serve

- Although the flick serve is hit upwards, the trajectory is much shallower than the high serve.

-

- Drive serve

- Drive serves are hit flat to the back of the receiver's service court. The drive serve is almost never used in elite games, because it relies on the receiver being unprepared. If the receiver reacts well, then the drive serve will be severely punished.

-

- Netshot

- A netshot is played into the opponent's forecourt, as close to the net as possible.

-

- Net kill

- The net kill is a shot which aims to kill the shuttle into the floor very close to the opponent's side of the net. The trajectory is almost vertical. It is commonly used to punish a poor low serve. The net kill is executed with a sudden, powerful 'tapping' motion produced by the wrist. This technique helps to eliminate the danger of hitting the net.

-

- Long kill

- The long kill is a net kill that is not so steep and therefore travels towards the rearcourt. A long kill is only used if a steeper kill cannot be played. It is similar to a net drive, but much more aggressive. The long kill can be played when returning a poor low serve.

-

- Net drive, net push, net lift

- These strokes are all the same as their midcourt counterparts, which are described below.

Strokes played from the midcourt

With the exception of the smash, all midcourt strokes are played with the shuttle either near the ground, or about net height, or slightly higher than net height. If the shuttle is ever high in the midcourt, a powerful smash will be played to finish the rally.

-

- Drive

- A drive is played when the shuttle is near net height, at the side of the player's body. Drives pass with pace into the opponent's midcourt or rearcourt. Although drives are played with pace, very high shuttle speed is not desirable because the shuttle will go out at the back. The trajectory of a drive is approximately flat.

-

- Half-court drive

- A drive played from in front of the body, usually hitting the shuttle from nearer the net than an ordinary drive.

-

- Push

- A push is played from the same situation as a drive, but played softly into the opponent's forecourt or front midcourt.

-

- Half-court push

- A push played from in front of the body, usually hitting the shuttle from nearer the net than an ordinary push.

-

- Lift

- A lift is played upwards to the back of the opponent's court. Midcourt lifts are most commonly played in response to a smash or well-placed push.

-

- Defensive lift

- A lift that is hit very high, so that the player gains time for recovery to a good base position. Defensive lifts, because of the flight characteristics of a shuttlecock, force the opponent to hit from the extreme back of the court.

-

- Attacking lift

- A lift that is hit more shallowly, so that the opponent is forced to move very quickly to prevent the shuttle from travelling behind him. Attacking lifts, because of the flight characteristics of a shuttlecock, may be intercepted slightly earlier than defensive lifts.

-

- Smash

- See the smash entry under rearcourt strokes, below. A midcourt smash is especially devastating.

Strokes played from the rearcourt

In the rearcourt, most strokes are played overhead. If the shuttle has dropped low in a player's rearcourt, so that he is unable to play an overhead stroke, then he is at a great disadvantage and is likely to lose the rally. The following strokes are all played from overhead:

-

- Clear

- A clear travels high and to the back of the opponent's rearcourt.

-

- Defensive clear

- A clear that is hit very high, so that the player gains time for recovery to a good base position. Defensive clears, because of the flight characteristics of a shuttlecock, force the opponent to hit from the extreme back of the court.

-

- Attacking clear

- A clear that is hit more shallowly, so that the opponent is forced to move very quickly to prevent the shuttle from travelling behind him. Attacking clears, because of the flight characteristics of a shuttlecock, may be intercepted slightly earlier than defensive clears.

-

- Smash

- A smash is a powerful stroke, played so that the shuttle travels steeply downwards at great speed into the opponent's midcourt.

-

- Jump smash

- A smash where the player jumps for height. The aim of a jump smash is to hit the smash at a steeper angle. Jump smashes are most common in men's doubles.

-

- Dropshot

- A dropshot is played downwards into the opponent's forecourt. Dropshots are usually disguised as smashes or clears, so that the opponent cannot anticipate the dropshot.

Advanced strokes

Advanced strokes are typically variations on a basic stroke. Often the purpose of an advanced stroke is to deceive the opponent, but advanced strokes may also be used to manipulate the flight path of the shuttlecock by introducing spin. Spin may cause the shuttlecock to follow a curved path and to dip more steeply as it falls.

A common technique for advanced strokes is slicing, where the shuttle is hit with an angled racket face. Often players brush the racket face around the shuttlecock to achieve more spin from their slice. Slices can be used to deceive opponents about the direction in which the player is going to hit the shuttle, and to make apparently powerful strokes that travel slowly (a dropshot may be disguised as a smash).

The lightness of modern rackets allows good players to play many strokes with a short swing. This skill provides opportunities for deception, because the player may pretend to play a soft stroke (such as a netshot), but then accelerate the racket at the last moment to play a more powerful stroke (such as a lift). This form of deception may also be reversed: players may pretend to play a powerful stoke, but then decelerate the racket at the last moment to play a soft stroke. In general, the former type of deception is more common towards the front of the court, whereas the latter type of deception is more common towards the back of the court.

Another technique for deception is double motion. In this technique, the player will make an initial motion towards the shuttlecock and then quickly withdraw the racket to hit the shuttlecock in a different direction. The aim is to show the opponent one direction but then quickly place the shuttlecock elsewhere. Some players may even use triple motion, although this is much rarer.

The following lists are not comprehensive; the scope for advanced strokes in badminton is large, in particular for deceptive strokes.

Sliced strokes

-

- Sliced dropshot

- A sliced dropshot allows the player to deceive his opponent about both the power and direction of the stroke. For example, the opponent may expect a straight clear or smash, but receive a crosscourt dropshot instead. Slicing the shuttlecock heavily will cause it to follow a curved path and dip more sharply as it crosses the net. There are two types of sliced dropshots - the normal slice and the reverse slice. The normal slice is played so that the shuttle goes left while the receiver thinks it goes right, however the reverse slice requires more of a brushing motion in order to slice the shuttle to the right while the opponent thinks the drop is being played to the left.

-

- Sliced smash

- A sliced smash allows the player to deceive his opponent about the direction of his smash. Slicing a smash also allows players to hit in directions that they might otherwise find impossible given their body position on the court.

-

- Spinning netshot (also called a tumbling netshot)

- Slicing underneath the shuttlecock allows the player to spin the shuttlecock so that it turns over itself several times as it crosses the net. The opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has corrected its flight. The spin also makes the shuttlecock fall tighter to the net.

-

- Sliced low serves

- Slicing the low serve may be used both for the straight low serve and for the wide low serve to the left side lines (for a righthander).

-

- Sliced straight low serve

- The purpose of slicing this serve is to not to change the direction, but to make the shuttle dip more steeply as it passes the net. The slicing may also cause the shuttle to wobble or shake in the air (introducing precession to the shuttle's flight), making it harder for the receiver to time and control his reply.

-

- Sliced wide low serve

- The purpose of slicing this serve is to deceive the opponent into believing that a straight serve, either low or flicked, is being played. For a righthander, the racket head will move at least slightly from left to right, but the shuttlecock will be sent to the left.

Deceptive strokes from the net

-

- Deceptive lift (hold and flick)

- The player holds the racket ready for a netshot, but at the last moment flicks the shuttlecock to the rearcout instead. This is mainly used in singles.

-

- Deceptive crosscourt netshot (breaking the wrist)

- The player holds the racket ready for a straight netshot, but at the last moment turns the racket face sideways to play the shuttle across the net instead. This is so called since the action required to perform this manoeuvre looks as if the wrist has been twisted badly in the opposite direction to the original movement; hence the name - breaking the wrist.

-

- Racket head fakes

- The player begins a stroke from the net in one direction, but then slightly alters the direction by rotating the racket head during the hitting. This can be used to make it harder for opponents to return net drives and pushes. A more pronounced racket head fake may be produced by using double motion, but this requires that the player have more time to perform the lengthier deception.

Specialised net kill techniques

-

- Short-action net kill

- This is a technique for killing shuttecocks that are close to the net tape. The player uses a very short forwards tapping motion to avoid hitting the net tape (which is a fault). The tapping action makes use of sudden tightening of the fingers to create power.

-

- Brush net kill

- This is a more difficult technique for killing shuttlecocks that are extremely close to the net tape. The player swipes the racket nearly parallel to the tape instead of hitting forwards. With a slight turning of the racket face during the swipe, the shuttlecock may be struck steeply downwards and in the direction of the swipe. For both forehand and backhand brush net kills, the swiping action is inwards to the centre.

Strategy

To win in badminton, players need to employ a wide variety of strokes in the right situations. These range from extraordinarily powerful jumping smashes to soft, delicate tumbling net returns. The smash is a powerful overhead stroke played steeply downwards into the middle or rear of the opponents' court; it is similar to a tennis serve, but much faster: the shuttlecock can travel at 300 km/h (186 mph). This is a very effective stroke, and pleases the crowds, but smashing is only one part of the game. Often rallies finish with a smash, but setting up the smash requires subtler strokes. For example, a netshot can force the opponent to lift the shuttle, which gives an opportunity to smash. If the netshot is tight and tumbling, then the opponent's lift will not reach the back of the court, which makes the subsequent smash much harder to return.

Deception is also important. Expert players make the preparation for many different strokes look identical, so that their opponents cannot guess which stroke will be played. For many strokes, the shuttlecock can be sliced to change its direction; this allows a player to move his racket in a different direction to the trajectory of the shuttlecock. If an opponent tries to anticipate the stroke, he will move in the wrong direction and may be unable to change his body momentum in time to reach the shuttlecock. In badminton you use your wrist a lot and pressing of fingers to a full-body smashes and clears.

Doubles: In doubles, each side has two players. Both sides will try to gain and maintain the attack, hitting downwards as much as possible. Usually one player will strive to stay at the back of the court and the other at the front, which is an optimal attacking position: the back player will smash and occasionally drop the shuttlecock to the net, and the front player will try to intercept any flat returns or returns to the net. Typical play involves hitting the shuttle in a trajectory as low and flat as possible, to avoid giving away the attack. A side that hits a high shot must prepare for a smash and retreat to a side-by-side defensive position, with each player covering half of the court. The first serve is usually a low serve to force the other side to lift the shuttle. A "flick serve", in which the player will pretend to serve low but hit it high to catch the receiver off-guard, is sporadically used throughout the game. Doubles is a game of speed, aggression, and agility.

Singles: Players will serve high to the far back end of the court, although at the international level low serves are now frequently used as well. The singles court is narrower than the doubles court, but the same length. Since one person needs to cover the entire court, singles tactics are based on forcing the opponent to move as much as possible; this means that singles shots are normally directed to the corners of the court. The depth of the court is exploited by combining clears (high shots to the back) with drops (soft downwards shots to the front). Smashing is less prominent in singles than in doubles because players are rarely in the ideal position to execute a smash, and smashing out of position leaves the smasher very vulnerable if the shot is returned. At high levels of play, singles demands extraordinary fitness. It is a game of patient tactical play, unlike the all-out aggression of doubles.

Mixed doubles: In this discipline, a man and a woman play as a doubles pair. Mixed doubles is similar to "level" doubles where pairs are of the same gender. In mixed doubles, both pairs try to maintain an attacking formation with the woman at the front and the man at the back. This is because the male players are substantially stronger, and can therefore produce more powerful smashes. As a result, mixed doubles requires greater tactical awareness and subtler positional play. Clever opponents will try to reverse the ideal position, by forcing the woman towards the back or the man towards the front. In order to protect against this danger, mixed players must be careful and systematic in their shot selection.

Governing bodies

The International Badminton Federation (IBF) is the internationally recognised governing body of the sport. The IBF headquarters are currently located in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Five regional confederations are associated with the IBF:

- Asia: Asian Badminton Confederation (ABC)

- Africa: Africa Badminton Federation (ABF)

- Americas: Pan American Badminton Confederation (North America and South America belong to the same confederation; PABC)

- Europe: European Badminton Union (EBU)

- Oceania: Oceania Badminton Confederation (OBC)

Competitions

There are several international competitions organized by the IBF. The Thomas Cup, a men's event, and the Uber Cup, a women's event, are the most important ones. The competitions take place once in two years. More than 50 national teams compete in qualifying tournaments within the scope of continental confederations for a place in the finals. The final tournament now involves 12 teams after an increase in 2004 (8 teams).

The Sudirman Cup is a mixed team event which is hosted once in two years starting from 1989. It is divide into seven group based on the performance of each country. Only the group that comes out best can win the event. The goal of the competition is to see the balance between the performances of men's badminton and women's badminton. Like soccer, it features the promotion and relegation system in every group.

In the individual competitions, badminton became a Summer Olympics sport at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Before that, it was a demonstration event in the 1972 and 1988 Summer Olympics. Only the 32 best badminton players in the world can participate in the competition based on their IBF ranking and each country can only submit three players to take part. The IBF World Championships is another event for players to show their true abilities. Only the best 64 players in the world, and a maximum of 3 from each country, can participate in any category. All these competitions are graded 7-star tournaments as well as the World Junior Championships.

In the regional events of each continent, mainly the competitions in Asia and Europe are gaining attention by the media because of the world's highest ranked players are participating in these continents. The Asian Badminton Championships (open for Asia players) and the European Badminton Championships (open for European players) are the two major regional events in the world.

As of the start of 2007, the IBF introduces the New Tournament Structure, known as Super Series. The 6-star tournament (level 2) will play in 12 countries with a minimum prize of USD$200,000 ( All-England, China, Denmark, France, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Switzerland). The participants limited to 32 players form previous 64. The players have to collect the points in ability to play in season-ending masters event, aas well as in China with a grand prize of USD$500,000.

With the introduction of the Super Series, IBF also standardized all the badminton events that start in 2007. The Grand Prix Gold open tournament (level 3, 4-star) will be offering USD$125,000 in prize money. 10 countries will be selected to organise a tournament in this event. The Grand Prix Gold event will combine with Grand Prix event (3-star), which offer the prize money of USD$50,000.

The fourth level event (A-star), known as International Challenge, offers USD$15,000. The International Series, offer USD$5,000, as the competition tries to gather more junior players into the tournament. The 28 and 55 tournaments are scheduled for both events respectively.

Records

The most powerful stroke in badminton is the smash, which is hit steeply downwards into the opponents' midcourt. The maximum speed of a smashed shuttlecock exceeds that of any other racket sport projectile. The recordings of this speed measure the initial speed of the shuttlecock immediately after it has left the player's racket.

Men's doubles player Fu Haifeng of China set the official world smash record of 332 km/h (206 mph) on June 3, 2005 in the Sudirman Cup. The fastest smash recorded in the singles competition was 298 km/h (185 mph) by Kenneth Jonassen of Denmark.

Comparisons with other racquet sports

Badminton is frequently compared to tennis. The following is a list of uncontentious comparisons:

- In tennis, the ball may bounce once before the player hits it; in badminton, the rally ends once the shuttlecock touches the floor.

- In tennis, the serve is dominant to the extent that the server is expected to win most of his service games; a break of service, where the server loses the game, is of major importance in a match. In badminton, however, the serving side and receiving side have approximately equal opportunity to win the rally.

- In tennis, the server is allowed two attempts to make a correct serve; in badminton, the server is allowed only one attempt.

- In tennis, a let is played on service if the ball hits the net tape; in badminton, there is no let on service.

- The tennis court is larger than the badminton court.

- Tennis rackets are much heavier than badminton rackets, which may weigh as little as 75 grams. Tennis balls are also heavier than shuttlecocks.

- The fastest recorded tennis stroke is Andy Roddick's 153 mph serve; the fastest recorded badminton stroke is Fu Haifeng's 206 mph smash.

Comparisons of speed and athletic requirements

Statistics such as the 206 mph smash speed, below, prompt badminton enthusiasts to make other comparisons that are more contentious. For example, it is often claimed that badminton is the fastest racket sport. Although badminton holds the record for the fastest initial speed of a racket sports projectile, the shuttlecock decelerates substantially faster than other projectiles such as tennis balls. In turn, this qualification must be qualified by consideration of the distance over which the shuttlecock travels: a smashed shuttlecock travels a shorter distance than a tennis ball during a serve. Badminton's claim as the fastest racket sport might also be based on reaction time requirements, but arguably table tennis requires even faster reaction times.

There is a strong case for arguing that badminton is more physically demanding than tennis, but such comparisons are difficult to make objectively due to the differing demands of the games. Some informal studies suggest that badminton players require much greater aerobic stamina than tennis players, but this has not been the subject of rigorous research.

A more balanced approach might suggest the following comparisons, although these also are subject to dispute:

- Badminton, especially singles, requires substantially greater aerobic stamina than tennis; the level of aerobic stamina required by badminton singles is similar to squash singles, although squash may have slightly higher aerobic requirements.

- Tennis requires greater upper body strength than badminton.

- Badminton requires greater leg strength than tennis, and badminton men's doubles probably requires greater leg strength than any other racket sport due to the demands of performing multiple consecutive jumping smashes.

- Badminton requires much greater explosive athleticism than tennis and somewhat greater than squash, with players required to jump for height or distance.

- Badminton requires significantly faster reaction times than either tennis or squash, although table tennis may require even faster reaction times. The fastest reactions in badminton are required in men's doubles, when returning a powerful smash.

Comparisons of technique

Badminton and tennis techniques differ substantially. The lightness of the shuttlecock and of badminton rackets allow badminton players to make use of the wrist and fingers much more than tennis players; in tennis the wrist is normally held stable, and playing with a mobile wrist may lead to injury. For the same reasons, badminton players can generate power from a short racket swing: for some strokes such as net kills, an elite player's swing may be less than 10cm. For strokes that require more power, a longer swing will typically be used, but the badminton racket swing will rarely be as long as a typical tennis swing.

It is often asserted that power in badminton strokes comes mainly from the wrist. This is a misconception and may be criticised for two reasons. First, it is strictly speaking a category error: the wrist is a joint, not a muscle; its movement is controlled by the forearm muscles. Second, wrist movements are weak when compared to forearm or upper arm movements. Badminton biomechanics have not been the subject of extensive scientific study, but some studies confirm the minor role of the wrist in power generation, and indicate that the major contributions to power come from internal and external rotations of the upper and lower arm. Modern coaching resources such as the Badminton England Technique DVD reflect these ideas by emphasising forearm rotation rather than wrist movements.

Distinctive characteristics of the shuttlecock

The shuttlecock differs greatly from the balls used in most racket sports.

Aerodynamic drag and stability

The feathers impart substantial drag, causing the shuttlecock to decelerate greatly over distance. The shuttlecock is also extremely aerodynamically stable: regardless of initial orientation, it will turn to fly cork-first, and remain in the cork-first orientation.

One consequence of the shuttlecock's drag is that it requires considerable skill to hit it the full length of the court, which is not the case for most racket sports. The drag also influences the flight path of a lifted (lobbed) shuttlecock: the parabola of its flight is heavily skewed so that it falls at a steeper angle than it rises. With very high serves, the shuttle may even fall vertically.

Spin

Balls may be spun to alter their bounce (for example, topspin and backspin in tennis), and players may slice the ball (strike it with an angled racket face) to produce such spin; but, since the shuttlecock is not allowed to bounce, this does not apply to badminton.

Slicing the shuttlecock so that it spins, however, does have applications, and some are peculiar to badminton. (See Basic strokes for an explanation of technical terms.)

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to travel in a different direction from the direction suggested by the player's racket or body movement. This is used to deceive opponents.

- Slicing the shuttlecock from the side may cause it to follow a slightly curved path (as seen from above), and the deceleration imparted by the spin causes sliced strokes to slow down more suddenly towards the end of their flight path. This can be used to create dropshots and smashes that dip more steeply after they pass the net.

- When playing a netshot, slicing underneath the shuttlecock may cause it to turn over itself (tumble) several times as it passes the net. This is called a spinning netshot or tumbling netshot. The opponent will be unwilling to address the shuttlecock until it has corrected its orientation.

Due to the way that its feathers overlap, a shuttlecock also has a slight natural spin about its axis of rotational symmetry. The spin is in an anticlockwise direction as seen from above when dropping a shuttle. This natural spin affects certain strokes: a tumbling netshot is more effective if the slicing action is from right to left, rather than from left to right.