Pi

2007 Schools Wikipedia Selection. Related subjects: Mathematics

The mathematical constant π is an irrational real number, approximately equal to 3.14159, which is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter in Euclidean geometry, and has many uses in mathematics, physics, and engineering. It is also known as Archimedes' constant (not to be confused with an Archimedes number) and as Ludolph's number.

The letter π

The name of the Greek letter π is pi, and this spelling is used in typographical contexts where the Greek letter is not available or where its usage could be problematic. When referring to this constant, the symbol π is always pronounced like "pie" in English, the conventional English pronunciation of the letter.

The constant is named "π" because it is the first letter of the Greek words περιφέρεια 'periphery' and περίμετρος 'perimeter', i.e. 'circumference'.

π is Unicode character U+03C0 (" greek small letter pi").

Definition

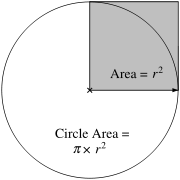

In Euclidean plane geometry, π is defined either as the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter, or as the ratio of a circle's area to the area of a square whose side is the radius. The constant π may be defined in other ways that avoid the concepts of arc length and area, for example as twice the smallest positive x for which cos(x) = 0. The formulæ below illustrate other (equivalent) definitions.

Numerical value

The numerical value of π truncated to 50 decimal places is:

- 3.14159 26535 89793 23846 26433 83279 50288 41971 69399 37510

With the 50 digits given here, the circumference of any circle that would fit in the observable universe (ignoring the curvature of space) could be computed with an error less than the size of a proton. Nevertheless, the exact value of π has an infinite decimal expansion: its decimal expansion never ends and does not repeat, since π is an irrational number (and indeed, a transcendental number). This infinite sequence of digits has fascinated mathematicians and laymen alike, and much effort over the last few centuries has been put into computing more digits and investigating the number's properties. Despite much analytical work, and supercomputer calculations that have determined over 1 trillion digits of π, no simple pattern in the digits has ever been found. Digits of π are available on many web pages, and there is software for calculating π to billions of digits on any personal computer. See history of numerical approximations of π.

Calculating π

Most formulas given for calculating the digits of π have desirable mathematical properties, but may be difficult to understand without a background in trigonometry and calculus. Nevertheless, it is possible to compute π using techniques involving only algebra and geometry.

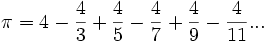

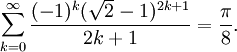

For example:

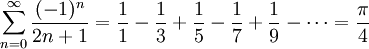

This series is easy to understand, but is impractical in use as it converges to π very slowly. It requires more than 600 terms just to narrow its value to 3.14 (two places), and billions of terms to achieve accuracy to ten places.

One common classroom activity for experimentally measuring the value of π involves drawing a large circle on graph paper, then measuring its approximate area by counting the number of cells inside the circle. Since the area of the circle is known to be

π can be derived using algebra:

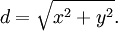

This process works mathematically as well as experimentally. If a circle with radius r is drawn with its centre at the point (0,0), any point whose distance from the origin is less than r will fall inside the circle. The Pythagorean theorem gives the distance from any point (x,y) to the centre:

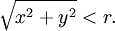

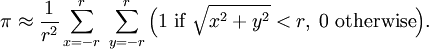

Mathematical "graph paper" is formed by imagining a 1x1 square centered around each point (x,y), where x and y are integers between -r and r. Squares whose centre resides inside the circle can then be counted by testing whether, for each point (x,y),

The total number of points satisfying that condition thus approximates the area of the circle, which then can be used to calculate an approximation of π.

Mathematically, this formula can be written:

In other words, begin by choosing a value for r. Consider all points (x,y) in which both x and y are integers between -r and r. Starting at 0, add 1 for each point whose distance to the origin (0,0) is less than r. When finished, divide the sum, representing the area of a circle of radius r, by r2 to find the approximation of π. Closer approximations can be produced by using larger values of r.

For example, if r is set to 2, then the points (-2,-2), (-2,-1), (-2,0), (-2,1), (-2,2), (-1,-2), (-1,-1), (-1,0), (-1,1), (-1,2), (0,-2), (0,-1), (0,0), (0,1), (0,2), (1,-2), (1,-1), (1,0), (1,1), (1,2), (2,-2), (2,-1), (2,0), (2,1), (2,2) are considered. The 9 points (-1,-1), (-1,0), (-1,1), (0,-1), (0,0), (0,1), (1,-1), (1,0), (1,1) are found to be inside the circle, so the approximate area is 9, and π is calculated to be approximately 2.25. Results for some values of r are shown in the table below:

| r | area | approximation of π |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 9 | 2.25 |

| 3 | 25 | 2.777778 |

| 4 | 45 | 2.8125 |

| 5 | 69 | 2.76 |

| 10 | 305 | 3.05 |

| 20 | 1245 | 3.1125 |

| 100 | 31397 | 3.1397 |

| 1000 | 3141521 | 3.141521 |

Similarly, the more complex approximations of π given below involve repeated calculations of some sort, yielding closer and closer approximations with increasing numbers of calculations.

Properties

The constant π is an irrational number; that is, it cannot be written as the ratio of two integers. This was proven in 1761 by Johann Heinrich Lambert.

Furthermore, π is also transcendental, as was proven by Ferdinand von Lindemann in 1882. This means that there is no polynomial with rational coefficients of which π is a root. An important consequence of the transcendence of π is the fact that it is not constructible. Because the coordinates of all points that can be constructed with compass and straightedge are constructible numbers, it is impossible to square the circle: that is, it is impossible to construct, using compass and straightedge alone, a square whose area is equal to the area of a given circle.

History

Use of the symbol π

Often William Jones' book A New Introduction to Mathematics from 1706 is cited as the first text where the Greek letter π was used for this constant, but this notation became particularly popular after Leonhard Euler adopted it some years later ( cf History of π).

Early approximations

-

- Main article: History of numerical approximations of π.

The value of π has been known in some form since antiquity. As early as the 19th century BC, Babylonian mathematicians were using π = 25⁄8, which is within 0.5% of the true value.

The Egyptian scribe Ahmes wrote the oldest known text to give an approximate value for π, citing a Middle Kingdom papyrus, corresponding to a value of 256 divided by 81 or 3.160.

It is sometimes claimed that the Bible states that π = 3, based on a passage in 1 Kings 7:23 giving measurements for a round basin as having a 10 cubit diameter and a 30 cubit circumference. Rabbi Nehemiah explained this by the diameter being from outside to outside while the circumference was the inner brim, which gives an approximate value of ~3.14; but it may suffice that the measurements are given in round numbers. Also, the basin may not have been exactly circular, though the verse claims that "...it was completely round." (NKJ)

Archimedes of Syracuse discovered, by considering the perimeters of 96-sided polygons inscribing a circle and inscribed by it, that π is between 223⁄71 and 22⁄7. The average of these two values is roughly 3.1419.

The Chinese mathematician Liu Hui computed π to 3.141014 (good to three decimal places) in AD 263 and suggested that 3.14 was a good approximation.

The Indian mathematician and astronomer Aryabhata in the 5th century gave the approximation π = 62832⁄20000 = 3.1416, correct when rounded off to four decimal places. He also acknowledged the fact that this was an approximation, which is quite advanced for the time period.

The Chinese mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi computed π to be between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927 and gave two approximations of π, 355⁄113 and 22⁄7, in the 5th century.

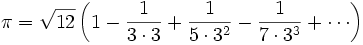

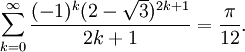

The Indian mathematician and astronomer Madhava of Sangamagrama in the 14th century computed the value of π after transforming the power series expansion of π⁄4 into the form

and using the first 21 terms of this series to compute a rational approximation of π correct to 11 decimal places as 3.14159265359. By adding a remainder term to the original power series of π⁄4, he was able to compute π to an accuracy of 13 decimal places.

The Persian astronomer Ghyath ad-din Jamshid Kashani (1350-1439) correctly computed π to 9 digits in the base of 60, which is equivalent to 16 decimal digits as:

- 2π = 6.2831853071795865

By 1610, the German mathematician Ludolph van Ceulen had finished computing the first 35 decimal places of π. It is said that he was so proud of this accomplishment that he had them inscribed on his tombstone.

In 1789, the Slovene mathematician Jurij Vega improved John Machin's formula from 1706 and calculated the first 140 decimal places for π of which the first 126 were correct and held the world record for 52 years until 1841, when William Rutherford calculated 208 decimal places of which the first 152 were correct.

The English amateur mathematician William Shanks, a man of independent means, spent over 20 years calculating π to 707 decimal places (accomplished in 1873). In 1944, D. F. Ferguson found that Shanks had made a mistake in the 528th decimal place, and that all succeeding digits were fallacious. By 1947, Ferguson had recalculated pi to 808 decimal places (with the aid of a mechanical desk calculator).

Numerical approximations

Due to the transcendental nature of π, there are no closed form expressions for the number in terms of algebraic numbers and functions. Formulæ for calculating π using elementary arithmetic invariably include notation such as "...", which indicates that the formula is really a formula for an infinite sequence of approximations to π. The more terms included in a calculation, the closer to π the result will get, but none of the results will be π exactly.

Consequently, numerical calculations must use approximations of π. For many purposes, 3.14 or 22/7 is close enough, although engineers often use 3.1416 (5 significant figures) or 3.14159 (6 significant figures) for more precision. The approximations 22/7 and 355/113, with 3 and 7 significant figures respectively, are obtained from the simple continued fraction expansion of π. The approximation 355⁄113 (3.1415929…) is the best one that may be expressed with a three-digit or four-digit numerator and denominator.

The earliest numerical approximation of π is almost certainly the value 3. In cases where little precision is required, it may be an acceptable substitute. That 3 is an underestimate follows from the fact that it is the ratio of the perimeter of an inscribed regular hexagon to the diameter of the circle.

All further improvements to the above mentioned "historical" approximations were done with the help of computers.

Formulæ

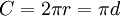

Geometry

The constant π appears in many formulæ in geometry involving circles and spheres.

| Geometrical shape | Formula |

|---|---|

| Circumference of circle of radius r and diameter d |  |

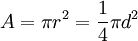

| Area of circle of radius r |  |

| Area of ellipse with semiaxes a and b |  |

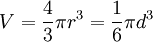

| Volume of sphere of radius r and diameter d |  |

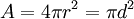

| Surface area of sphere of radius r and diameter d |  |

| Volume of cylinder of height h and radius r |  |

| Surface area of cylinder of height h and radius r |  |

| Volume of cone of height h and radius r |  |

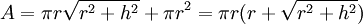

| Surface area of cone of height h and radius r |  |

All of these formulae are a consequence of the formula for circumference. For example, the area of a circle of radius R can be accumulated by summing annuli of infinitesimal width using the integral  . The others concern a surface or solid of revolution.

. The others concern a surface or solid of revolution.

Also, the angle measure of 180° ( degrees) is equal to π radians.

Analysis

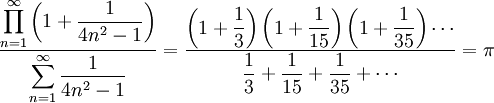

Many formulas in analysis contain π, including infinite series (and infinite product) representations, integrals, and so-called special functions.

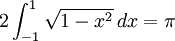

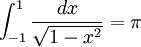

- The area of the unit disc:

- Half the circumference of the unit circle:

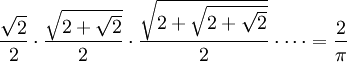

- François Viète, 1593 ( proof):

- Leibniz' formula ( proof):

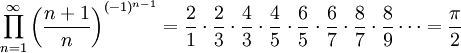

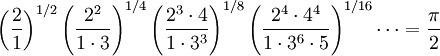

- Wallis product, 1655 ( proof):

- Faster product (see Sondow, 2005 and Sondow web page)

-

- where the nth factor is the 2nth root of the product

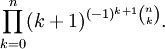

- Symmetric formula (see Sondow, 1997)

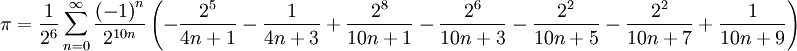

- Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe algorithm (See Bailey, 1997 and Bailey web page)

- Chebyshev series Y. Luke, Math. Tabl. Aids Comp. 11 (1957) 16

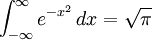

- An integral formula from calculus (see also Error function and Normal distribution):

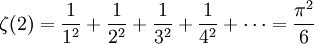

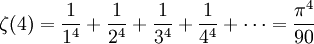

- Basel problem, first solved by Euler (see also Riemann zeta function):

-

- and generally, ζ(2n) is a rational multiple of π2n for positive integer n

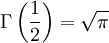

- Gamma function evaluated at 1/2:

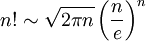

- Stirling's approximation:

- Euler's identity (called by Richard Feynman "the most remarkable formula in mathematics"):

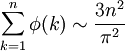

- A property of Euler's totient function (see also Farey sequence):

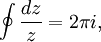

- An application of the residue theorem

-

- where the path of integration is a closed curve around the origin, traversed in the standard anticlockwise direction.

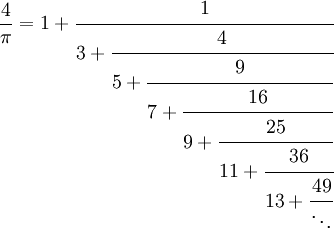

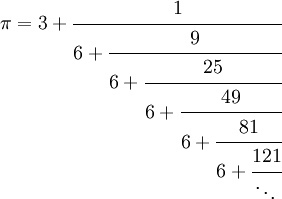

Continued fractions

Besides its simple continued-fraction representation [3; 7, 15, 1, 292, 1, 1, …], which displays no discernible pattern, π has many generalized continued-fraction representations generated by a simple rule, including these two.

(Other representations are available at The Wolfram Functions Site.)

Number theory

Some results from number theory:

- The probability that two randomly chosen integers are coprime is 6/π2.

- The probability that a randomly chosen integer is square-free is 6/π2.

- The average number of ways to write a positive integer as the sum of two perfect squares (order matters but not sign) is π/4.

Here, "probability", "average", and "random" are taken in a limiting sense, e.g. we consider the probability for the set of integers {1, 2, 3,…, N}, and then take the limit as N approaches infinity.

- The product of (1 − 1/p2) over the primes, p, is 6/π2.

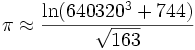

The theory of elliptic curves and complex multiplication derives the approximation

which is valid to about 30 digits.

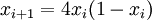

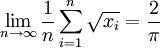

Dynamical systems and ergodic theory

Consider the recurrence relation

Then for almost every initial value x0 in the unit interval [0,1],

This recurrence relation is the logistic map with parameter r = 4, known from dynamical systems theory. See also: ergodic theory.

Physics

The number π appears routinely in equations describing fundamental principles of the Universe, due in no small part to its relationship to the nature of the circle and, correspondingly, spherical coordinate systems.

- The cosmological constant:

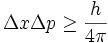

- Heisenberg's uncertainty principle:

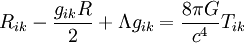

- Einstein's field equation of general relativity:

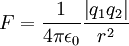

- Coulomb's law for the electric force:

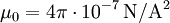

- Magnetic permeability of free space:

Probability and statistics

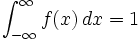

In probability and statistics, there are many distributions whose formulæ contain π, including:

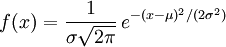

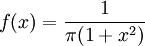

- probability density function (pdf) for the normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ:

- pdf for the (standard) Cauchy distribution:

Note that since  , for any pdf f(x), the above formulæ can be used to produce other integral formulae for π.

, for any pdf f(x), the above formulæ can be used to produce other integral formulae for π.

A semi-interesting empirical approximation of π is based on Buffon's needle problem. Consider dropping a needle of length L repeatedly on a surface containing parallel lines drawn S units apart (with S > L). If the needle is dropped n times and x of those times it comes to rest crossing a line (x > 0), then one may approximate π using:

[As a practical matter, this approximation is poor and converges very slowly.]

Another approximation of π is to throw points randomly into a quarter of a circle with radius 1 that is inscribed in a square of length 1. π, the area of a unit circle, is then approximated as 4*(points in the quarter circle) / (total points).

Efficient methods

In the early years of the computer, the first expansion of π to 100,000 decimal places was computed by Maryland mathematician Dr. Daniel Shanks and his team at the United States Naval Research Laboratory (N.R.L.) in 1961. Dr. Shanks's son Oliver Shanks, also a mathematician, states that there is no family connection to William Shanks, and in fact, his family's roots are in Central Europe.

Daniel Shanks and his team used two different power series for calculating the digital of π. For one it was known that any error would produce a value slightly high, and for the other, it was known that any error would produce a value slightly low. And hence, as long as the two series produced the same digits, there was a very high confidence that they were correct. The first 100,000 digits of π were published by the US Naval Research Laboratory

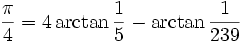

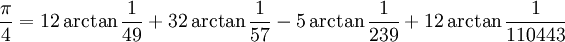

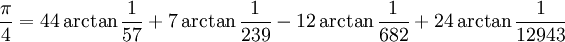

None of the formulæ given above can serve as an efficient way of approximating π. For fast calculations, one may use a formula such as Machin's:

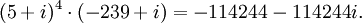

together with the Taylor series expansion of the function arctan(x). This formula is most easily verified using polar coordinates of complex numbers, starting with

Formulæ of this kind are known as Machin-like formulae.

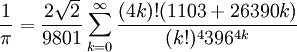

Many other expressions for π were developed and published by the incredibly intuitive Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. He worked with mathematician Godfrey Harold Hardy in England for a number of years.

Extremely long decimal expansions of π are typically computed with the Gauss-Legendre algorithm and Borwein's algorithm; the Salamin-Brent algorithm which was invented in 1976 has also been used.

The first one million digits of π and 1/π are available from Project Gutenberg (see external links below). The record as at December 2002 by Yasumasa Kanada of Tokyo University stands at 1,241,100,000,000 digits, which were computed in September 2002 on a 64-node Hitachi supercomputer with 1 terabyte of main memory, which carries out 2 trillion operations per second, nearly twice as many as the computer used for the previous record (206 billion digits). The following Machin-like formulæ were used for this:

- K. Takano ( 1982).

- F. C. W. Störmer ( 1896).

These approximations have so many digits that they are no longer of any practical use, except for testing new supercomputers. (Normality of π will always depend on the infinite string of digits on the end, not on any finite computation.)

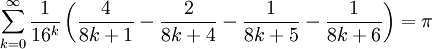

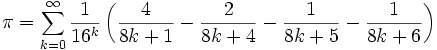

In 1997, David H. Bailey, Peter Borwein and Simon Plouffe published a paper (Bailey, 1997) on a new formula for π as an infinite series:

This formula permits one to fairly readily compute the kth binary or hexadecimal digit of π, without having to compute the preceding k − 1 digits. Bailey's website contains the derivation as well as implementations in various programming languages. The PiHex project computed 64-bits around the quadrillionth bit of π (which turns out to be 0).

Fabrice Bellard claims to have beaten the efficiency record set by Bailey, Borwein, and Plouffe with his formula to calculate binary digits of π :

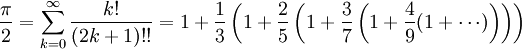

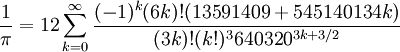

Other formulæ that have been used to compute estimates of π include:

- Ramanujan.

This converges extraordinarily rapidly. Ramanujan's work is the basis for the fastest algorithms used, as of the turn of the millennium, to calculate π.

- David Chudnovsky and Gregory Chudnovsky.

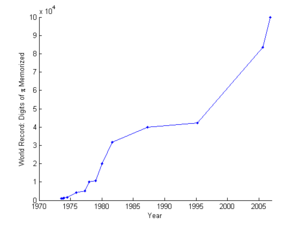

Memorizing digits

Even long before computers have calculated π, memorizing a record number of digits became an obsession for some people. The current world record is 100,000 decimal places, set on October 3, 2006 by Akira Haraguchi. The previous record (83,431) was set by the same person on July 2, 2005 , and the record previous to that (42,195) was held by Hiroyuki Goto.

There are many ways to memorize π, including the use of piems, which are poems that represent π in a way such that the length of each word (in letters) represents a digit. Here is an example of a piem: How I need a drink, alcoholic in nature (or: of course), after the heavy lectures involving quantum mechanics. Notice how the first word has 3 letters, the second word has 1, the third has 4, the fourth has 1, the fifth has 5, and so on. The Cadaeic Cadenza contains the first 3834 digits of π in this manner. Piems are related to the entire field of humorous yet serious study that involves the use of mnemonic techniques to remember the digits of π, known as piphilology. See Pi mnemonics for examples. In other languages there are similar methods of memorization. However, this method proves inefficient for large memorizations of pi. Other methods include remembering "patterns" in the numbers (for instance, the "year" 1971 appears in the first fifty digits of pi).

Open questions

The most pressing open question about π is whether it is a normal number -- whether any digit block occurs in the expansion of π just as often as one would statistically expect if the digits had been produced completely "randomly", and that this is true in every base, not just base 10. Current knowledge on this point is very weak; e.g., it is not even known which of the digits 0,…,9 occur infinitely often in the decimal expansion of π.

Bailey and Crandall showed in 2000 that the existence of the above mentioned Bailey-Borwein-Plouffe formula and similar formulæ imply that the normality in base 2 of π and various other constants can be reduced to a plausible conjecture of chaos theory. See Bailey's above mentioned web site for details.

It is also unknown whether π and e are algebraically independent. However it is known that at least one of πe and π + e is transcendental (see Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem).

Naturality

In non-Euclidean geometry the sum of the angles of a triangle may be more or less than π radians, and the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter may also differ from π. This does not change the definition of π, but it does affect many formulæ in which π appears. So, in particular, π is not affected by the shape of the universe; it is not a physical constant but a mathematical constant defined independently of any physical measurements. Nonetheless, it occurs often in physics.

For example, consider Coulomb's law (SI units)

.

.

Here, 4πr2 is just the surface area of sphere of radius r. In this form, it is a convenient way of describing the inverse square relationship of the force at a distance r from a point source. It would of course be possible to describe this law in other, but less convenient ways, or in some cases more convenient. If Planck charge is used, it can be written as

and thus eliminate the need for π.

Trivia

- March 14 (3/14 in U.S. date format) marks Pi Day which is celebrated by many lovers of π. Incidentally, it is also Einstein's birthday.

- On July 22, Pi Approximation Day is celebrated (22/7 - in European date format - is a popular approximation of π). Note some other days are celebrated as Pi Approximation Day.

- 355⁄113 (~3.1415929) is sometimes jokingly referred to as "not π, but an incredible simulation!"

- Singer Kate Bush's 2005 album " Aerial" contains a song titled "π", in which she sings π to its 137th decimal place; however, for an unknown reason, she omits the 79th to 100th decimal places. She was preceded in this achievement by several years by a Swedish indie math lyrics artist under the moniker Matthew Matics, who loses track of the decimals at about the same point in the series.

- Swedish jazz musician Karl Sjölin once wrote, recorded and performed a song based on and called Pi. The song followed the decimals of Pi, with every number representing a certain note. For example 1=C, 2=D, 3=E etc. The song was then performed as a jazz song, thus making the harmony more liberal.

- John Harrison (1693–1776) (famed for winning the longitude prize), devised a meantone temperament musical tuning system derived from π, now called Lucy Tuning.

- Users of the A9.com search engine were eligible for an amazon.com program offering discounts of (π/2)% on purchases.

- The Heywood Banks song "Eighteen Wheels on a Big Rig" has the singer(s) count pi in the final verse; they reach "eight hundred billion" before going into the chorus.

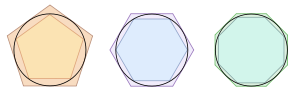

- In 1932, Stanisław Gołąb proved that, if a unit disk is defined using a non-standard norm as "distance", the ratio of circumference to diameter will always be between 3 and 4; these values are attained if and only if the unit "circle" has the shape of a regular hexagon or a parallelogram respectively. See unit disc for details.

- John Squire (of The Stone Roses) mentions π in a song written for his second band The Seahorses called "Something Tells Me". The song was recorded in full by the full band, and appears on the bootleg of the never released second-album recordings. The song ends with the lyrics, "What's the secret of life? It's 3.14159265, yeah yeah!!"

- Hard 'n Phirm's fourth track on Horses and Grasses is "Pi" (and is preceded by "An Intro", which discusses the topic like an educational television program). Many digits are recited through it, and a video appeared online inspired by it.

- There is a building in the Googleplex numbered 3.14159...

- In 1897, the Indiana General Assembly passed a bill from which it could be deduced that pi was equal to 3.2 or other incorrect values. The Indiana Senate postponed the bill indefinitely, preventing it from becoming law.

- The Bloodhound Gang have a song called "Three Point One Four"

- Daniel Tammet holds the European record for remembering and recounting pi, recounting it to its 22,514th digit in just over 5 hours on 14 March 2004.

- In the Weebl and Bob episode " riot", Weebl states that he only fights "for 3.14 pies".